How to become a Trainer in France

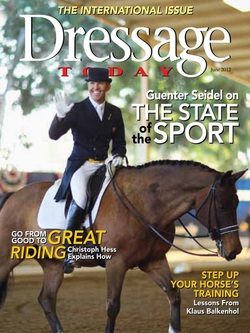

Dressage Today / June 2012 by Pierre Cousyn

Located outside of Saumur, France, just southwest of Paris on the Loire River is one of the largest and most famous riding schools in the world—the French National School of Equitation (Ecole Nationale d’Equitation [ENE]). It is filled with well-trained horses and instructors striving to pass on the classical system of riding to students. Students go to the ENE to learn to ride and teach and receive the diploma that will allow them to work as professional trainers and instructors.

To be a qualified trainer in France means you can teach to a certain level, and your diploma is a guarantee of your skills, knowledge and safety. Can you imagine going to a doctor who did not go to medical school? Of course not.

Well, in France, we think the same standards should apply in all fields. I received my diploma at the ENE, but it is not a simple undertaking. First, I had to qualify for the selection trial by having a high-school diploma and passing seven federal riding exams in a riding school that follows the rules and criteria of the French Riding Federation.

The test at every level has a riding section followed by a theory section, which addresses all aspects of food, care, equipment, etc. Passing the seventh exam is the most important because it allowed me to compete in official competitions at the lowest level for one year. After that, my results were good enough to allow me to continue to the next level, but if rider does not do well, he must stay at the same level for another year. No one can a skip a level. This is federation law.

Next, I needed to earn yet another diploma called a tronc commun (common origin) that is delivered by the sport minister. This exam tested my knowledge on athletics in general. I studied anatomy, physiology, sports nutrition, the impact of sport on the body, different training programs, regulations of sports, psychology for athletes and coaching in general. When I had all these credentials, then I was ready to sit for the entrance exam to attend the ENE.

There were 140 applicants for 16 students at the ENE that year. There was a one-day selection trial that began at 7 a.m. and we had two hours to write about a riding topic. At 9, I rode a dressage test, a jumping course and a cross-country course. For each test I rode horses I hadn’t ridden before and that was stressful. During lunch, half the applicants were asked to leave. In the afternoon, I had a motivational interview and a psychology test. Then I had to wait several months to receive the results and find out (happily) that I had been accepted.

My program started on Sept. 1 and went through the end of the following June. The first week, we received a different horse for each discipline and a young horse. We would ride and train these horses for the year and ride them in the final exam. The horse I was given to work with for jumping was given to me on trial because she had a huge bascule and was a bit of a challenge. When she jumped, the rider would get thrown forward and it was hard to lean back at the landing, especially over the bigger jumps. Because of the techniques I learned from Professor Magien, I successfully worked with the mare all year and performed well with her in the final exam.

Located outside of Saumur, France, just southwest of Paris on the Loire River is one of the largest and most famous riding schools in the world—the French National School of Equitation (Ecole Nationale d’Equitation [ENE]). It is filled with well-trained horses and instructors striving to pass on the classical system of riding to students. Students go to the ENE to learn to ride and teach and receive the diploma that will allow them to work as professional trainers and instructors.

To be a qualified trainer in France means you can teach to a certain level, and your diploma is a guarantee of your skills, knowledge and safety. Can you imagine going to a doctor who did not go to medical school? Of course not.

Well, in France, we think the same standards should apply in all fields. I received my diploma at the ENE, but it is not a simple undertaking. First, I had to qualify for the selection trial by having a high-school diploma and passing seven federal riding exams in a riding school that follows the rules and criteria of the French Riding Federation.

The test at every level has a riding section followed by a theory section, which addresses all aspects of food, care, equipment, etc. Passing the seventh exam is the most important because it allowed me to compete in official competitions at the lowest level for one year. After that, my results were good enough to allow me to continue to the next level, but if rider does not do well, he must stay at the same level for another year. No one can a skip a level. This is federation law.

Next, I needed to earn yet another diploma called a tronc commun (common origin) that is delivered by the sport minister. This exam tested my knowledge on athletics in general. I studied anatomy, physiology, sports nutrition, the impact of sport on the body, different training programs, regulations of sports, psychology for athletes and coaching in general. When I had all these credentials, then I was ready to sit for the entrance exam to attend the ENE.

There were 140 applicants for 16 students at the ENE that year. There was a one-day selection trial that began at 7 a.m. and we had two hours to write about a riding topic. At 9, I rode a dressage test, a jumping course and a cross-country course. For each test I rode horses I hadn’t ridden before and that was stressful. During lunch, half the applicants were asked to leave. In the afternoon, I had a motivational interview and a psychology test. Then I had to wait several months to receive the results and find out (happily) that I had been accepted.

My program started on Sept. 1 and went through the end of the following June. The first week, we received a different horse for each discipline and a young horse. We would ride and train these horses for the year and ride them in the final exam. The horse I was given to work with for jumping was given to me on trial because she had a huge bascule and was a bit of a challenge. When she jumped, the rider would get thrown forward and it was hard to lean back at the landing, especially over the bigger jumps. Because of the techniques I learned from Professor Magien, I successfully worked with the mare all year and performed well with her in the final exam.

The day started early. From 7 to 8 we cleaned our horses. At 8, we started with the improvement of the seat. We used a different horse every day always working on something specific like riding without stirrups in the woods, jumping on the longe or anything that would challenge our seats. Then, we practiced the other disciplines until noon. After lunch, we were in the classroom learning riding theory and how to teach. We were divided into two groups. Some students were on horses with a student acting as the instructor. The second group stood on the side with our professor, watching and taking notes. Then we went back to the classroom to analyze the lesson. Finally, one of us had to write a lesson plan and give the lesson the next day. It had to include an introduction and a step-by-step plan. We had to explain the what, why and how for every step. Col. Pierre Durand was the director of the ENE and the ecuyer en chef (chief of the elite group) during the time I studied there.

He was respected for competing at two Olympic Games and multiple Nations Cups in eventing and jumping. He was also respected for the way he managed the Cadre Noir, the elite riders who train the classical highschool movements or haute école. All the students were in awe of him and a bit nervous in his presence. I remember one day when Col. Durand rode into the arena during our teacher training session. He was in a two-point seat position with his hands either wide open or at different levels or different lengths. We wondered what he was doing. He stopped in front of our groupand asked us what we saw? Everyone was quiet. His response was, “To have your hands quiet, low and together is when the education of your horse is finished and well done. But to get there you may need to change the classical hand position to a different, more extravagant one to solve a problem. Don’t be afraid to do this but always remember to come back to the classical position when the problem is solved.”

I remember another day when Col. Durand admonished a student for coming to class with dirty boots. He instructed the student that the next time he had dirty boots on he would have to leave class for one week. It was explained to us that if you do not have respect for your equipment, then you do not have respect for yourself or for your horse. So, as trainers, we learned that we must always be good examples to our students. Such is the training that includes discipline and respect. On Saturday afternoons and Sundays we rested and completed homework—theory, writing essays, reading classical books and preparing for the final exam. Sometimes we competed in events. A week before the final exam, our seat-improvement instructor decided to help us relax. We got on our horses and followed as he galloped through the woods jumping anything he thought might be fun. We did this without stirrups, and our legs were like noodles when we finished. For that time period, we certainly forgot about the final. The final exam began with writing a three-hour essay. On the following days, we demonstrated our skills in all the disciplines. We first rode and then had an interview with the jury to discuss what we had just demonstrated. The jury asked all kinds of questions. They wanted to know if we could explain what we were doing, fix any problems and teach it to another. After riding again, we had interviews on barn management, horse care and our project that involved the organization of a show. But all that only counted for 50 percent of the test. The other 50 percent was the teaching test.

A half hour before my turn, I had to get the topic of my future lesson out of a hat and then write my lesson plan. After teaching the lesson, I had to defend it to the jury. The jury wanted to know if I was in control and fit as a trainer.These courses are taught in French, but ENE also offers a similar 10-month class taught in English culminating in an international diploma. This program begins every October. Applicants must be at least 18 years old and riding at the “M” level (about Third Level dressage) in all disciplines. The school also offers shorter, single-discipline courses in English without a diploma.The philosophy of the school is that you must be able to do it, be able to show it to your students and finally be able to teach it. I also learned that a happy relationship between horse and rider is the only way dressage makes sense

He was respected for competing at two Olympic Games and multiple Nations Cups in eventing and jumping. He was also respected for the way he managed the Cadre Noir, the elite riders who train the classical highschool movements or haute école. All the students were in awe of him and a bit nervous in his presence. I remember one day when Col. Durand rode into the arena during our teacher training session. He was in a two-point seat position with his hands either wide open or at different levels or different lengths. We wondered what he was doing. He stopped in front of our groupand asked us what we saw? Everyone was quiet. His response was, “To have your hands quiet, low and together is when the education of your horse is finished and well done. But to get there you may need to change the classical hand position to a different, more extravagant one to solve a problem. Don’t be afraid to do this but always remember to come back to the classical position when the problem is solved.”

I remember another day when Col. Durand admonished a student for coming to class with dirty boots. He instructed the student that the next time he had dirty boots on he would have to leave class for one week. It was explained to us that if you do not have respect for your equipment, then you do not have respect for yourself or for your horse. So, as trainers, we learned that we must always be good examples to our students. Such is the training that includes discipline and respect. On Saturday afternoons and Sundays we rested and completed homework—theory, writing essays, reading classical books and preparing for the final exam. Sometimes we competed in events. A week before the final exam, our seat-improvement instructor decided to help us relax. We got on our horses and followed as he galloped through the woods jumping anything he thought might be fun. We did this without stirrups, and our legs were like noodles when we finished. For that time period, we certainly forgot about the final. The final exam began with writing a three-hour essay. On the following days, we demonstrated our skills in all the disciplines. We first rode and then had an interview with the jury to discuss what we had just demonstrated. The jury asked all kinds of questions. They wanted to know if we could explain what we were doing, fix any problems and teach it to another. After riding again, we had interviews on barn management, horse care and our project that involved the organization of a show. But all that only counted for 50 percent of the test. The other 50 percent was the teaching test.

A half hour before my turn, I had to get the topic of my future lesson out of a hat and then write my lesson plan. After teaching the lesson, I had to defend it to the jury. The jury wanted to know if I was in control and fit as a trainer.These courses are taught in French, but ENE also offers a similar 10-month class taught in English culminating in an international diploma. This program begins every October. Applicants must be at least 18 years old and riding at the “M” level (about Third Level dressage) in all disciplines. The school also offers shorter, single-discipline courses in English without a diploma.The philosophy of the school is that you must be able to do it, be able to show it to your students and finally be able to teach it. I also learned that a happy relationship between horse and rider is the only way dressage makes sense